Sparrow Bones (Part III)

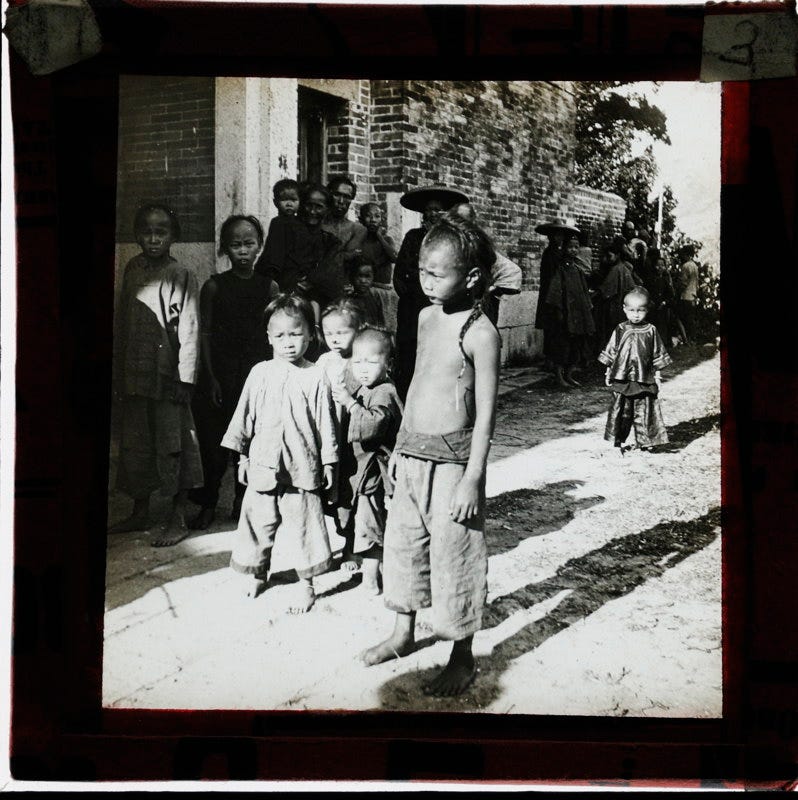

A Girl's Life During the Great Chinese Famine

Disclaimer: This is a work of historical fiction. While the characters are made up, the events are based on records collected during this time. You can learn more about the history in the footnotes.

ICYMI:

Sparrow Bones Part I

Sparrow Bones Part II

No time to read? Listen to it instead. :)

It’s April, 1960. The soft pattering of rain surrounds The Girl as she squats on the edge of the deserted fields, slinging handful after handful of mud into her mouth1. The cold is so numbing that she can hardly feel the gravelly texture chaffing her tongue nor savor the hints of iron that flavor each bite. Just last week there had been wild grass and brambles to boil into a mush. Now, even that is gone.

She hears shouting in the distance. The sound of bone snapping. More shouting. But she hardly pays it any attention. The mob of hunters is growing bolder and bolder by the day—especially with so many of the local authorities either dead or starving—but so far they’ve only attacked outsiders traveling through their village and not the villagers themselves2.

She grimaces as she forces herself to swallow another mouthful of mud. If she had even an ounce more strength, she would sneak over after the dust settled and see if she could scavenge some leftovers. This morning, she’d talked with the leader of the mob about her plan, and he’d been friendly with her, assuring her that he and his followers would play their part to the teeth.

“You have my word,” Uncle Tian had said with a toothy grin. “Grandpa Zhou will be…well taken care of.”

As she swallows another mouthful of mud, she surveys the drowned fields with weary eyes. The water has risen high enough to cover a grown person lying down. Just a few days ago, she’d seen Auntie Shu Ling dragging a body from the other end of the fields—probably some poor child who’d keeled over and didn’t have enough strength to pull itself out of the water3. The next morning, she smelled broth drifting down Auntie Shu Ling’s street.

She eyes a knotted tree branch jutting out of the water, and wonders whether she might be do the same if she’d been the one to find the child.

Her head spins and she feels like retching on standing up. It doesn’t help that her limbs ache with a patchwork of bruises, some as thin as the tip of a fingernail while others as large as coins. Though he hasn’t penetrated her in over a week, she can still feel invisible fingers groping her cervix, like worms digging into her flesh, each time she closes her eyes.

At least the old man has kept his side of the bargain4, she reminds herself as she begins trekking back to the village. The watery porridge made from Grandpa Zhou’s extra stock of rice was usually enough to keep her conscious, but for what she’s about to do tomorrow night, she needed to fill her belly with something more.

Even if that something means the earth itself. She bends down and swallows another mouthful of mud just for good measure.

The shouting fades as she reaches the maze of slanted, wooden huts. Even with most of the doors bolted, the stench of decay is overwhelming.

Jin Yi stands by the village gate, wrapped in an oversized coat. They walk together in silence for a minute before Jin Yi finally sighs, “You don’t have to do this, you know.”

The Girl shakes her head. “I already talked with Uncle Tian. He said yes.”

“How much do you trust him?” Jin Yi asks, canting her head.

“As much as I dare,” she replies. “What other option do I have? You know Grandpa Zhou will turn on us the moment the rice runs out. Maybe even before then.”

“I know…I just worry.”

As they round a corner, they notice a man with a bristly beard lying slumped against the side of a house. Jin Yi stiffens beside her, and The Girl realizes it’s the official who had stripped them naked and forced them to work the furnaces till their skins peeled. Heat burns her cheeks. She is just about to spit in his face when he looks up. Those eyes…they can’t belong to the same person, can they? They’re only a few years older than her own.

“How is he enjoying the lighter?” The man rasps.

“Not much now that the cigarettes are gone,” The Girl replies cautiously.

His lips curve just enough to reveal a crescent of yellowed teeth. “There would be more if the Soviets hadn’t taken them. And our money. And our crops. And our steel5.”

The Girl thinks about the abandoned furnaces, their once fiery mouths now as cold as the grave. “They weren’t the ones who took our clothes,” she whispers. “And our dignity.”

“I did what I had to do,” he replies in a weary voice. “For our country. For our future.”

“A future built on the backs of starving, naked women is no future at all,” The Girl whispers.

Before she can go on, Jin Yi kicks dust into his eyes. “I hope you get turned to steam buns.” She spits, fists shaking in rage. “Large, white, fluffy steam buns. Enough to feed all of China.”

“I would hope so too,” he answers, his voice cracking with genuine regret as The Girl pulls Jin Yi away, “except there’s no flour to make them.”

When they’ve walked some distance, Jin Yi says, “I meant what I said.”

The man’s eyes flash across The Girl’s mind and she sighs, “Even if he got turned into steam buns, I bet he’d only taste bitter.”

She frowns as they turn the corner onto her street. She can hear Grandpa Zhou singing merrily to the tune of bubbling water. Strange. Grandpa Zhou never cooks. She glances at Jin Yi, and the two friends quicken their steps.

Growing grains at noon,

Sweat drips into the soil.

Who would have thought the food on your plate,

each and every grain, came from hard work?6

The Girl flings open the damp curtain shielding the doorway, and her blood turns icy in her veins.

“STOP!” She screams.

Grandpa Zhou smiles over his shoulder but does not move the blade dangling hardly a foot above her brother.

As she steps forward, Grandpa Zhou tightens his grip around her brother’s neck and lowers the knife a few more inches. Her brother scrunches his face into a sob but the rag around his mouth stifles his cries. Clutched between his fingers is the wooden sparrow, its dull eyes turned away from her.

“Uh-uh.”

The Girl stops. The world is tilting, faster and faster. She tries to gulp air, but for some reason, her lungs refuse to inflate. She gasps and leans against the doorway. Her heart pounds so fiercely, it feels as if her ribs might crack any minute.

Besides her, Jin Yi is as still as marble, her face a pale tallow. Grandpa Zhou nods at her and growls, “Run along before things get ugly.”

Jin Yi gives The Girl a remorseful look before turning on her heels.

When she’s out of earshot, he lowers the knife another inch and sings in a teasing drawl, “Who would have thought the food on your plate, each and every grain, came from hard work?”

“Take me,” she whispers. “Take my arm. Take my leg. I’ll chop them off myself. Just don’t hurt him, please.”

A sly grin creeps across his face. “Ahhh, but I thought you enjoyed human flesh, my dear—”

She opens her mouth to protest, but he cuts her off. “At least, that’s what I heard from Uncle Tian.”

Her body tenses as if someone had poured freezing water over her head. Uncle Tian? But…their deal…he couldn’t have…

“You know what went wrong with this plan of yours?” Grandpa Zhou swings the knife carelessly back and forth. “Hubris. You think you understand how adults work, but,” he glances at her, shaking his head, “you’re just a little kid. A dirty, pathetic, useless thing. Another mouth to feed in a world that already has too many mouths.”

“But Uncle Tian—I was helping him—”

Grandpa Zhou doubles over with laughter. The Girl’s heart skips a beat as he nearly drops the knife on her brother.

After regaining control, he sneers, “Well, I guess little kids are good for one thing—you’re all so amusing.” He picks up the knife and continues. “Poor, stupid girl. Did you really think Uncle Tian was on your side? Do you know what he did barely an hour after your meeting with him?”

He points to the now-empty rice sack lying by the doorway. The girl stares at it, nonplussed. It’d been half full just this morning. “He rushed to me and said, ‘I’ll trade you—secret for rice.’ When I asked what the secret was, he replied, ‘Your life. She’s planning to split your skull in your sleep and offer you to us in exchange for protection.’”

He gives her a pointed look. “You know what he said next? He and his kind have all the meat they need. What they lack is rice.” He lets out a bark of laughter. “That’s all it takes to turn a man’s loyalty. Rice.”

“Uncle Tian’s lying!” The Girl racks her brain, trying to find some excuse. “You said it yourself—I’m just a stupid, little girl. How could I have come up with such a plan?”

"I said you don’t understand how adults work not that you don’t know how to act according to human nature.” He smirks and pinches her brother’s cheeks till his fingernails whiten.

“You saw a chance to get me killed, so you went for it—Self-preservation is human nature. That I can respect. But to have faith in another human being, to hope in their promises—now, that is childish. You saw the way Jin Yi ran. Do you really think there are such things as friendship or love? If you want to grow up, do this—get your head out of your ass and take a good look at the world around you.”

He cackles as he brings the blade down in one, decisive swing. The Girl shrieks and lunges for his arm. She knocks the knife from his hands, but not before it grazes her brother’s head, leaving a long, crimson gash.

Her mind races. Grandpa Zhou’s eyes narrow. His lips curl into a growl. She is running out of time. There must be something she can say. Something she can do. Why don’t the gods strike him dead on the spot? Tears blur her vision as he tosses her onto the ground. This can’t be the end! She won’t let it be the end.

She hisses as her hand touches something scalding hot. In his carelessness, Grandpa Zhou had also knocked over the pot of boiling water. Something flickers in the back of her mind as she watches the water stream across the floor, like a river…like a flooded field.

“I found a piglet!” She shouts, pushing herself to her feet. She clings to Grandpa Zhou’s arms, trying and failing to keep him from raising his knife-hand. “I found a piglet. Drowned in the fields. I can take you to it.”

Grandpa Zhou pauses, and The Girl seizes the opportunity to place herself between him and her brother. “I came back to tell you about it, but it-it slipped my mind when I-when I came in.”

When Grandpa Zhou still doesn’t say anything, she gestures to the mud splattered across her face and down her front, “I tried hauling it out of the mud, but it was too big for me. If we don’t hurry, someone else will take it.”

She watches Grandpa Zhou carefully, her heart racing. What do the lines between his brows mean? Was he flaring his nostrils in contemplation or anger?

“Liar,” he spits. “There hasn’t been a pig in the village since last spring.”

The Girl replies, “I saw it fall out the back of a delivery truck this morning. Please, if we don’t hurry, we’ll never get this chance again!”

Grandpa Zhou’s mouth hardens as he lifts the blade to her neck. “You better not be lying.”

The Girl hugs her brother, pressing her cheeks against his, then she removes the rag from his mouth. Slowly, he curls his fingers around her index. Tears blur her vision, but she wills them away as she picks him up and follows Grandpa Zhou out of the house.

If the gods won’t protect them, then she’ll do it herself.

When they arrive at the field where The Girl had squatted half an hour earlier, stuffing herself with mud, Grandpa Zhou brandishes the knife at the water and asks, “So? Where is it?”

She sets her brother down a safe distance from the field but not before prying the wooden sparrow from his hands. He whimpers in protest, and she gives him a reassuring smile.

“There!” She calls, pointing at some indefinite point not too far from the path. “It’s so small, it’s probably blending with the silt.”

Grandpa Zhou steps forward and shudders as the icy water laps his ankles. A knotted branch juts from the water, and he leans against it like a cane.

“I still don’t see it.”

The Girl approaches from behind, her grip tightening on the wooden sparrow. She sucks in a sharp breath as she joins him in the water. “Are you sure?” She asks through chattering teeth. “It’s right there. Right besides the branch.”

As Grandpa Zhou turns to meet her, The Girl hooks his temple with the sparrow.

Grandpa Zhou stumbles but, to her dismay, doesn’t drop the knife. “Wha—”

She swings again, this time aiming for his neck. Grandpa Zhou makes a spluttering sound and blindly slashes the knife through the air, missing The Girl’s eyes by a few centimeters. She yelps and jumps back, tripping over a rock. Something sharp jabs her spine and for a second she wonders if the knife has finally found its mark.

But…no. Grandpa Zhou was still an arm’s length away, swaying unsteadily on his feet…The branch! She drops the bird and gropes for the knotted branch. It sinks slightly into the silt when she leans against it. Good. That means it can be loosened. Clutching it with numb fingers, she pulls and pulls. Her muscles scream. Her chest tightens as time ticks away. She can hear splashing getting closer and closer. Still, the branch would not relent.

“Come here!”

She screams as calloused hands grab her throat, shoving her beneath the water. She tries to yell for help but all that comes out is a stream of bubbles. Darkness begins to bleed across the edge of her vision. She claws at the hands around her throat but her twiggy fingers are nothing against Grandpa Zhou’s iron grip. He’s saying something, but she can’t hear what.

Wailing rises in the distance—lost and lonely. Her brother…she’d failed him…She thrashes harder. Everything is burning. Her lungs. Her head. Her guts. Something hard and bony smashes into her teeth. Iron fills her mouth, and she screams, water rushing down her throat. Through the murkiness, she can tell Grandpa Zhou is raising something above his head. Something gleaming.

As she reaches towards the surface one last time, her fingers brush against that familiar, grainy texture—the sparrow! She grabs it and thrusts it upward. Something sharp embeds itself into the wood. Gathering all her remaining strength, she pulls the bird along with the knife from Grandpa Zhou’s grip and tosses them as far away as she can manage.

The darkness is nearly complete now. She can feel herself sinking…sinking. Oddly enough, the sensation is strangely comforting. Like snuggling under a warm blanket after a long day of hard work. Tiny pinpricks of light materialize, growing in number and brilliance. The stars. She wonders if she has finally reached the home of the gods when she feels someone pulling her upwards. Could it be her mother?

“Mama!” She tries to shout. “Mama! I’m home!”

Suddenly, she’s coughing and gasping. Air rushes into her lungs. Her head lolls. Every inch of her is shaking. Even trying to open her eyelids takes effort.

“Are you alright?” Someone yells, shaking her. “Can you breathe?”

The Girl twists onto her side and retches. She manages to open her eyelids just a fraction. The world is a foggy gray with shapeless blots of color shifting here and there. Tears sting her eyes as she retches some more. The arms holding her tighten. Someone is calling her name. The wailing has returned, growing fiercer and fiercer by the second. Her head swells with the sound, like a balloon about to pop.

When the burning has subsided somewhat, The Girl lifts her head and meets her friend’s eyes.

“You came back,” she wheezes.

Jin Yi nods and gently helps her into a sitting position. “I can’t let you enjoy all this meat by yourself.” Her tone is so flat that The Girl can’t tell if she’s joking or not.

She points to a silhouette lying face down in the water. The Girl nearly retches again when she sees the knife handle protruding from the side of Grandpa Zhou’s neck. A great cloud of pink is blooming around the wound, mingling with the particles of silt in an almost mesmerizing dance. She turns away before the tears can come again. How can something so horrific be so beautiful?

“It’ll taste bitter,” she whispers.

“Only if you let it rot.” Jin Yi replies. “Come on. Your brother’s already wailed himself hoarse.”

The Girl lets Jin Yi lead her to the spot where her brother is lying. She curls up beside him and offers him her hand. He closes his eyes as he sucks the mud from her fingertips. Jin Yi returns to the water while The Girl teeters on the edge of consciousness and sleep, singing softly to the sound of bones cracking in the distance.

Growing grains at noon,

Sweat drips into the soil.

Who would have thought the food on your plate,

each and every grain, came from hard work?

Jin Yi returns just as the sun sinks into the earth. She sits The Girl and her brother upright then feeds them strip after strip of warm flesh. The three of them chew in silence, watching the world darken.

Suddenly, her brother croaks, “Oops, you died.”

The Girl and Jin Yi start.

“Oops, you died,” he repeats.

The Girl looks up and sees the little wooden sparrow bobbing on the waters, its beak pointing toward the faint strip of red bloodying the horizon.

“Fly,” she whispers. “Fly home. You’re free now.”

Sparrow Bones (Part IV)

Disclaimer: This is a work of historical fiction. While the characters are made up, the events are based on records collected during this time. You can learn more about the history in the footnotes. ICYMI: Sparrow Bones Part I Sparrow Bones Part II Sparrow Bones Part III

During the worst of the famine, people would eat mud just to fill their bellies with something. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

In Gansu province, there are tales of people killing and eating outsiders who passed through their village. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/01/china-great-famine-book-tombstone

There are reports of people digging up the corpses (strangers as well as family members) and eating them. Sometimes they’d do this as a team, sometimes they’d do this individually. https://www.refworld.org/docid/52e0d5e35.html

People would trade anything they could for food, from clothing to furniture to even children and sex. Xun Zhou, Forgotten Voices of Mao’s Great Famine, 1958-1962: An Oral History, (Connecticut: Yale University Press, 2013)

In China, natural disasters and Russian treachery—rather than irrational government policies or corruption—are often blamed for the famine. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/09/books/review/tombstone-the-great-chinese-famine-1958-1962-by-yang-jisheng.html

“Sympathy for Peasants” is a poem written by the poet Li Shen (born 772 A.D.) in the Tang dynasty during a time of significant political unrest. The poem conveys people’s tendency to overlook the farmers whose labor keeps society functioning while simultaneously calling for people to appreciate each grain of food on their plate. https://www.fluentu.com/blog/chinese/chinese-poems/

Macy - you have created a really beautiful story here. The best stories contain some darkness and an honesty about the human condition. I admire your ability to craft fiction as it is a skill I don't readily posses. Keep up the great work.

Disturbing, but good. I appreciate that you managed to get disturbing in by appealing to realism and human nature, how we act in desperation when we're starving.