Sparrow Bones (Part I)

A Girl's Life during the Great Chinese Famine

No time to read? Listen to it instead. :)

Disclaimer: This is a work of historical fiction. While the characters are made up, the events are based on records collected during this time period. You can learn more about the history of the famine in the footnotes.

It’s 19591. The Girl whistles a tune as she wrings the neck of a baby sparrow, her voice drowning out its shrill cry and the snap that comes after. She beams with crooked teeth as she plunges her hands into the sweet, brown soil, steaming with clods of cow dung, for she knows better times are ahead.

She kneads the dung into the earth then scoops out a small handful of the rich stuff and tucks the sparrow along with a sprout of sweet potato inside.

In reality, it’s a sprout that has been snipped in half—stem, leaf, root, and all. By dividing the plants, the village leaders can make the fields look fuller than they really are—just in case a party official visits one of these days2. Though she sees their drooping leaves and feels their moisture sticking to her fingers, she whistles nonetheless, for she knows the Party cannot be wrong3.

The Girl looks up at the sound of tinkling laughter to see her three-year-old brother tottering on the edge of the field, pointing at a yellow butterfly. Auntie Shu Ling, who’s in charge of the communal nursery, looms watchfully over him and several other children. They’re combing the fields for the four pests the state mandated must be destroyed: mosquitoes, rats, flies, and sparrows, especially sparrows4.

She sees her brother shriek at a sparrow as it flies overhead, scaring it from landing among the crops.

Pride squeezes her heart, and she pumps her fist into the air. “Long live Chairman Mao!”

On the other end of the field, her best friend, Jin Yi, begins warbling a song and soon, the air is abuzz with the voices of a hundred farmers:

This is the heroic Motherland This is the place where I grew up On this stretch of ancient land There is youthful vigor everywhere.5

Though her lips are cracked from the heat, The Girl joins them for fear of being called unzealous.

As she sings she wipes her forehead on the tattered sleeve of her cotton uniform—its once vibrant blue now the color of an overcast dawn. She imagines unfolding the uniform a decade from now and flashing it back and forth before her brother, his face as bright as a New Year’s dumpling.

“I was born into this uniform at the beginning of the world,” she’ll say, “during a time when we had to work till our fingers bled and the earth was our mattress and the clouds our blankets—unlike your generation now. Now, all you know is how to lounge in the sun and fatten yourselves on milk and sugar.”

She imagines him staring at her with doubtful eyes and exclaiming, “But how’s that possible when we’ve always been rich?”

Then, he will gesture at the infinite steaming cauldrons lining the collective banquet hall; the hunks of pork hanging from hooks, anointing the heads of anyone who passed under them with warm oil; the deliriously sweet scent of honey perfuming the air; the children weaving through the crowds, with banners of Chairman Mao’s face trailing behind them like a phoenx tail; the endless sounds of slurping, of chattering, of laughing, of bone dice clacking, of wine cups clinking, of heels tapping, of fires roaring, of…

The sun bloodies the earth as it sinks into the horizon.

The Girl’s limbs tremble with exhaustion, but she dares not stop until it is completely dark6. She can smell the scent of rice porridge taunting her from afar. Her head swims. Patterns dance across her vision. She thinks she can hear faraway laughter. Maybe she has already reached the hall with the endless cauldrons and phoenix tail banners.

When she comes to, she realizes she’d been nibbling on the root of a sweet potato for the past half-hour and spits it out in terror. She shreds the chewed tuber into innocuous pieces then joins the string of people marching toward the edge of the field. Soon, Jin Yi catches up to her, still humming the song they’d sung earlier.

The air is electric by the time they reach the food line.

“Did you hear—”

“—melon the size of a tractor7!”

Jin Yi grabs The Girl’s hand and shoulders her way toward where the conversation is liveliest.

“30 kilograms (66 pounds)—”

“That’s impossible,” Jin Yi declares.

“It says so in the New China News Agency.”

The Girl steps on Jin Yi’s foot to keep her from saying anything that might get her in trouble.

“Just look at the size of that thing!”

“That’s nothing. They should show our fields.”

“All that’ll be left of them will be bird droppings if you don’t catch those sparrows.”

“Let me see!”

Jin Yi snatches the newspaper from a boy about their age. The Girl leans in and gasps. There, on the front page, printed in scratchy black and white, is the biggest melon she has ever seen. It looks as if the people in the photo had uprooted one of the nearby mountains and were parading it around on a palanquin.

“How come we didn’t have such good fortune?” The Girl wonders.

“Cause you can’t grow crops with dreams,” an elderly woman grunts over her shoulders.

She thinks about the pieces of shredded tuber sticking to the bottom of her shoes and doesn’t reply.

The conversation about the monster melon persists even as she stumbles her way around the figures huddled around makeshift tables of tin sheets, clay pots, and, sometimes, tables of just their imagination.

Upon reaching her usual spot, she finds Grandpa Zhou (though he doesn’t have any grandchildren, everyone calls him Grandpa) pounding the dirt with gnarled fists.

She squats down across from him and tightens the clutch on her bowl, though its rim burns her fingers.

“Not enough hours in the field,” he spits, “that’s why we haven’t seen the same success. And look at this .”

He pulls a copy of the newspaper from under Auntie Shu Ling’s bowl and points at a different picture. “Chairman Mao visiting a village in Henan. I heard from my cousin, that their harvest was so bountiful that even their dogs and pigs disdain leftovers8.”

The Girl glances at the picture but doesn’t meet Grandpa Zhou’s eyes.

Jin Yi shovels porridge into her mouth and scoffs, “Well, it’s not like we keep our leftovers either.”

“At least not the parts that are bad,” Auntie Shu Ling mutters, poking her chopsticks at a strip of wilted rhubarb.

“Didn’t you hear the report yesterday?” Jin Yi laughs. “Thirty-times increase in production since last year. So, who cares? Waste whatever you like.”

“My cousin-in-law did mention that our granaries are near bursting,” Auntie Shu Ling replies thoughtfully, though she doesn’t stop prodding at the wilted rhubarb.

The Girl feels a nudge on her elbow and looks down to find a pair of brown, shining eyes staring back at her. She lifts her brother onto her lap and drops a clump of rhubarb, some of the pieces as thin as wires, into his gaping mouth. She presses her nose against his scalp and inhales his sweetness.

Grandpa Zhou chuckles and slips a piece of yellow candy between the boy’s tiny fingers. With one hand he brings a pipe to his lips, his brows furrowed with concentration and pleasure. With the other, he touches something under the table, slowly, back and forth.

Since their parents passed away not long after her brother was born, Grandpa Zhou has been caring for them like his own. At least that’s what The Girl repeats to herself as she closes her thighs to keep his hand from venturing deeper.

“Mark my words,” he says, his pipe bouncing between his teeth, “this isn’t the last we’ll hear of Henan.”

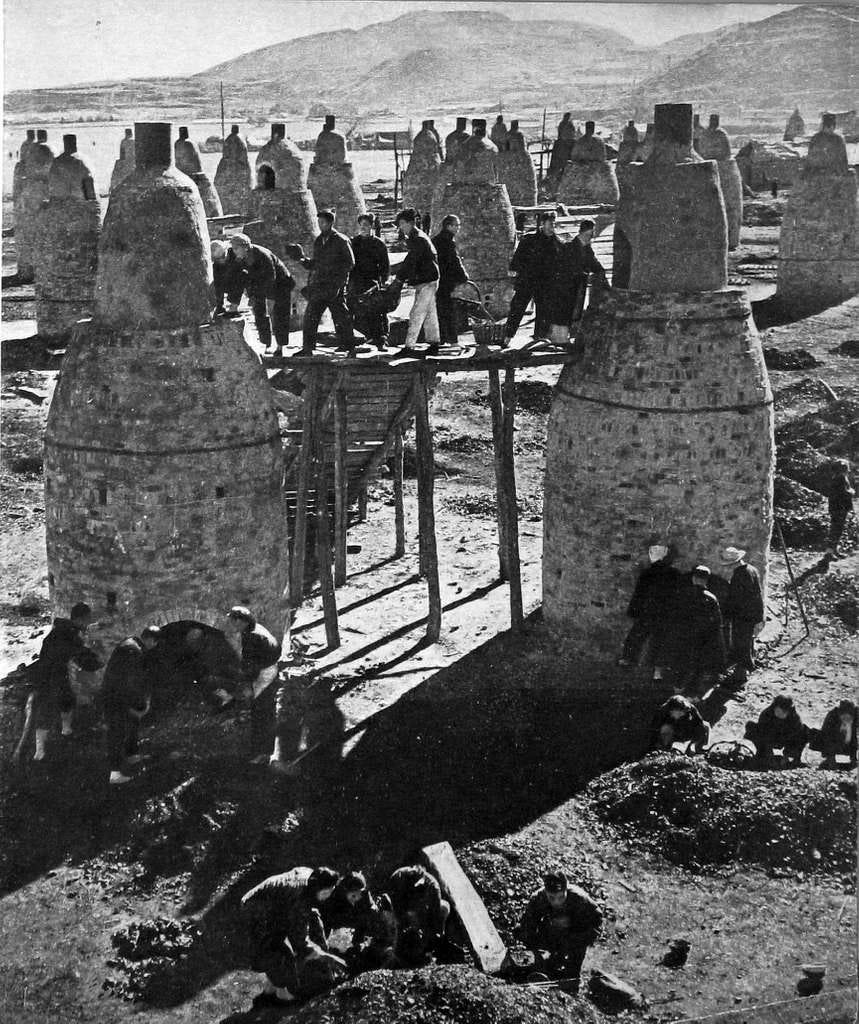

A cry suddenly pierces the air. The people around her hush. Heads lower. Chopsticks fall still. A door slams. There’s shouting. Clothing being torn. Something heavy falling. The crunch of a nose being broken. Three shadows elongate. The Girl hugs her brother against her chest, shielding his eyes with her hands.

She does not look up from her bowl when two officials with nail-studded clubs haul a naked, elderly man past her table. She does not need to see the blood pooling in his collarbones and the strips of skin hanging like bedsheets down his sides to know that they are there. She does not flinch when she hears the man blubbering like an infant and the club connecting with his skull. Once. Twice. Again. And Again.

Neither do the people around her, for they know this will happen tomorrow and the next day and the day after—if not in their village then in the villages around them and in the villages surrounding those villages and in the villages surrounding even those9.

When the man’s cries become too faint to hear, Jin Yi slams her fists on the table. “Down with the Rightists.”

The Girl responds like clockwork. “Long live Chairman Mao.”

“Long live Chairman Mao,” her brother chortles, a bit of yellow drool dribbling down his chin.

The Girl gazes into her bowl. The rhubarb has dyed the content a queasy pink, the same color of brains splattered across brick dust. She lifts the bowl to her lips and drinks anyway.

That night she and her brother snuggle on a fraying bamboo mat10 stretched in the fields, among dozens of other sleeping figures.

She tries counting the stars, like she does most nights, beginning with the cluster in the farthest region of the upper right corner. She painstakingly makes it up to fifty before a lack of knowledge forces her to stop and try again with another cluster, this time in the upper left.

As she counts, she recalls the stories her mother told her about the gods that live among the stars in palaces of pearls and gold so bright you can hardly bear to look at them. Her eyes close to the sound of singing frogs and rustling leaves. She wonders if it’s blaspheme to want to pluck the stars from the heavens and pop them into her mouth as if they are grains of rice rather than the homes of gods.

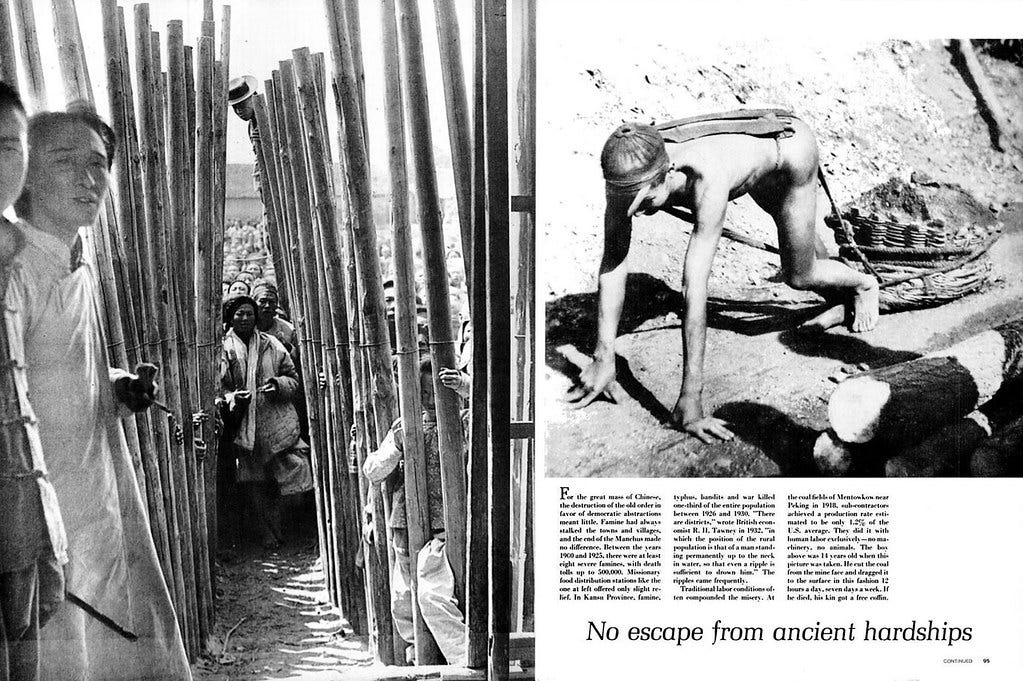

The Girl arrives at the furnace field before the frogs have stopped singing and before the last stars have faded, yet dirty plumes of smoke are already choking the air. The furnaces cover the plain like a phalanx of clay bullets someone had carefully laid out on an enormous table. Two or three workers attend to each one, feeding the flames or pouring liquid fire into casts, their backs stooped as if in solemn worship.

The air in front of her wavers like a mirage as she approaches her designated furnace, the one overseen by Grandpa Zhou. Soot powder his face, making him blend into the night. A wet towel, that will become as stiff as cardboard in a couple of hours, hugs his bald head. He weaves his way around the pots, pans, and iron farm tools littering his workspace to reach her.

“Table legs?” he asks.

“Coffin doors,” she replies, dumping a load of timber at his feet11. “Some of the men are chopping them up for us.”

“What happened the tables?” He asks.

“All gone. And the kitchen hands say if we cut down any more brush, there won’t be any wood left for cooking and heating come winter time. All that’s left is…well…this.”

“Chairman Mao warned it won’t be easy overtaking the Soviets and Great Britain12,” he grunts, gesturing proudly at the fresh mound of iron bars leaning against the side of the furnace. “But, hah! The best part is, they probably won’t even see this coming.”

He spits on the ground.

In reality, all he’s created in his twelve months of smelting are pig iron, only good for clogging railroad yards, rather than the steel that’s supposed to go towards making cars, trains, and farm equipment. But of course, he doesn’t know this nor is there anyone to tell him.

“Yes, Grandpa Zhou,” The Girl responds softly.

“Poor child,” he smiles, inching so close she can feel his breath, “it’s a good thing Grandpa is here to keep you safe, eh?”

His eyes rest on her chest, where two small hills have recently begun to push against the fabric.

She bows her head respectfully and races past the clay bullets, past the pools of liquid fire. She does not slow down till she reaches the other end of the furnace field where she is greeted by the cold ringing of metal as it slices through the air. She joins the semi-circle of girls huddled around Uncle Tian as he smashes the door of a particularly exquisite coffin with curved rims. The ebony paint hardly looks chipped. She wonders if the coffin is even a year old.

“Hey! Let’s get some help here!”

She squints against the rising sun and sees Jin Yi waving her arms not far off. As The Girl draws closer, she notices a dozen men and women digging with bent metal buckets and broken shovelheads.

Jin Yi passes her an ax, its head so dull, she can skate her fingers along its edge a dozen times without cutting herself. Since the erection of the backyard furnaces, every scrap of metal, no matter how small or weak has been given up for smelting. To be holding an ax, one that’s actually intact, felt nearly illegal13.

“That one over there,” Jin Yi points to the ditch nearest to them. “Try to avoid cutting them, if you can. Give us a shout when you’re ready for us to come collect the pieces.”

The Girl drops the ax on the coffin and slowly lowers herself into the ditch. It’s so narrow that there’s barely enough space for her to turn around. In fact, only two-thirds of the coffin has been excavated. The rest she’ll have to pry out of the dirt with her hands or the ax.

She raises the ax above her head and swings with all her might, for she knows that with every swing she is getting closer to the hall of infinite cauldrons and the phoenix tail banners.

But as is the case for regular people like you and me and The Girl, it’s what she does not know that’s more important.

She does not know that at this very moment, a tax official at the capital is reviewing her village’s grossly exaggerated harvest report and deciding on a tax amount that would virtually rob her and her people of their entire food supply14.

She does not know that high in the misty summits of Lushan, Minister of Defense Peng Dehuai15 is handing Chairman Mao a letter that would place Peng under house arrest for daring to suggest that harvest reports from across the country might not reflect reality.

She does not know that though the granary in her village and thousands of other villages will soon stand empty for years, the state will continue exporting grain for profit and as foreign aid rather than admit its policies had failed16.

At last, the cover of the coffin splits. The Girl swings again and this time, an entire section of the cover caves in. Breathing heavily, she reaches in to retrieve the fallen pieces, but rather than feel jagged wood, her fingers brush against something cold and pulpy.

She does not jump back. She does not gasp. Her eyes barely widen. Instead, she swings the ax again, enlarging the hole.

Gaping back at her is a woman she does not recognize or remember, not because of the maggots squirming on her face or because her nose has caved in like a rotten squash but because The Girl doesn’t care. To her, this is just another task of another day of another week of another month.

As she moves one of the boards, the woman’s head tilts back and her left eyelid slides open. For a second, The Girl thinks she can see her reflection in the filmy pupil. But the moment passes as quickly as it comes. She lifts her arms and keeps swinging.

END PART ONE

Sparrow Bones (Part II)

It’s February, 1960. The Girl hums softly to herself as she dips a chunk of salt into a pot of meekly boiling water and swirls it once, twice along its edge. She sways gently to the tune as she tosses in a handful of millet grains and three pieces of shriveled, sweet potato leaves, for she knows that better times are still ahead. They have to be.

The famine began in 1958, worsened by late1959 and ended in 1961. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1127087/#:~:text=Forty%20years%20ago%20China%20was,births%20were%20lost%20or%20postponed.

When Mao visited villages, local leaders would use sneaky methods such as transplanting crops along his route to make their harvests appear more bountiful than they actually were. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

The Great Leap Forward is a five year campaign launched by the Chinese communist party in 1958 to accelerate industrial and agricultural problems. It, along with the previous five year plan during which private property was effectively abolished, catalyzed the Great Chinese Famine. https://www.britannica.com/money/topic/Great-Leap-Forward

Part of the Great Leap Forward campaign was eliminating the “four pests": flies, mosquitoes, sparrows, and rats. Unfortunately, sparrows are an integral part of the ecosystem. Without them, the insect population, particularly locusts, flourished, decimating harvests and contributing heavily to the Great Chinese Famine. https://www.discovermagazine.com/health/paved-with-good-intentions-mao-tse-tungs-four-pests-disaster

https://www.sin80.com/en/work/my-motherland

Workers would often labor until sunset and sometimes even late into the night. This was called “catching the moon and stars”. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

In the original news article that inspired this part of the plot, the “melon” was actually a 60-kilogram “pumpkin”, but since sweet potatoes are usually planted in the spring, making this switch was necessary for plot consistency. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward

At the start of the Great Leap Forward, people were so ecstatic on hearing about the supposed bumper harvests happening across the country, they would often dump leftovers and gorge themselves in eating contests. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

In 1957, Mao invited criticism from scholars and intellectuals: “Let a hundred flowers bloom. Let a hundred schools of thought contend.” When criticism did begin flooding the central government, he then launched the Anti-Rightists campaign that same year, which executed and “re-educated” hundreds of thousands of critics. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/the-silence-that-preceded-chinas-great-leap-into-famine-51898077/

To save travel time, people would often eat and sleep in the fields. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

Keeping the furnaces running resulted in the loss of nearly 10% of China’s forests at the time. The demand for wood was so high, the people would burn doors, furniture, and even coffins. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

At the start of the Great Leap Forward, Mao promised China would become the world’s leading producer of steel within the next five years. That’s an impossible 2,000% increase in production. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

Rather than have the people mine for iron ores, party officials instructed them to create steel from any iron supplements they can get their hands on, from cooking utensils to woks to farming tools. Because the people lacked the skill and knowledge for smelting, they could only produce low grade pig iron, which would simply be thrown away. https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/great-leap-forward/

https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Peng-Dehuai

https://alphahistory.com/chineserevolution/great-chinese-famine/

Thank you for writing this, it's heartbreaking and really places us back to that time and place.

My husband and his family emigrated from China and talk about those days, but it's hard to imagine the scale of this famine and how it affected so many people... and you're right, we don't talk about it enough.

Such An important aspect of history to write about. Thank you for this