Sparrow Bones (Part II)

A Girl's Life during the Great Chinese Famine

Disclaimer: This is a work of historical fiction. While the characters are made up, the events are based on records collected during this time. You can learn more about the history in the footnotes.

Read Part I of “Sparrow Bones” here.

No time to read? Listen to it instead. :)

It’s February, 1960. The Girl hums softly to herself as she dips a chunk of salt into a pot of meekly boiling water and swirls it once, twice along its edge1. She sways gently to the tune as she tosses in a handful of millet grains and three pieces of shriveled, sweet potato leaves, for she knows that better times are still ahead. They have to be.

Even though it’s so cold that she’s afraid the salt will stick to her tongue if she dares to take one lick. Even though her shoes are tattered to the point that she can feel the icy dirt through the soles.

Even though the village granary has become so depleted that they’ve disbanded the communal kitchen and started rationing food for individuals again2. Even though it’s been seven weeks since the local officials promised that trucks carrying food and blankets will soon arrive.

Even though she’s so frail, her ribs stick out like mountain ranges and her eyes are starting to look too big for her head. Even though she’s just used the last of her millet ration and tomorrow she will have to scavenge for wild grass to survive another day.

Her brother plays with a crudely crafted wooden sparrow by the stove. The Girl sniffs the stale air and hums louder. She hasn’t been inside her family home since she’d started sleeping in the fields last spring to maximize farming time.

Apart from the pot, the sagging stove, and the wooden sparrow, everything else from her past had been carted to the furnace fields or handed to local officials to be shared communally3. The pot and stove she’d stolen from the house of a neighbor who’d died last year and the sparrow…she stops humming as she watches her brother.

“Oops! You died!” Her brother laughs, chucking the bird against the wall. It bounces back to him, and he chucks it again. “Oops! You died!”

The sparrow had been the last thing her father made before the fever took him. She couldn’t bear to part with it. But as for whether she had accidentally forgotten it in the house or she had purposely refused to deliver it to the furnaces, she can’t recall. Or maybe she doesn’t want to recall. Even just seeing her brother suck on its grainy head makes her feel sick. All it takes is one person whispering her name and the word “rightist” in the same sentence to an official for her to end up—

“Hey, you!”

Someone grabs her neck. She turns and stumbles, but the person would not let go. Her brother wails and crawls for the farthest corner. Panic swells. The man punches her. Fireworks blaze across her vision. She tries to scream but all that comes out is a strangled gasp. She digs her nails into the stranger’s arms, and he punches her across the jaw again. She twists to dodge his next attack but his fists find her anyway, this time in the guts.

Something rips and she hits the ground hard. Suddenly, she can feel weak sunlight gingerly caressing parts of her body it has never touched before. The man flings her against the wall, where she lies in a crumpled heap, too weary and too afraid to get up. When the fireworks have ceased, she looks down and sees goosebumps blooming across her breasts and legs.

“Get up,” the man snarls.

Though her head is swimming, she recognizes him as one of the local authorities, his once oily beard now reduced to a handful of sad bristles.

“Why are you—”

The official steps close, his bare toes inches from her throat. “Get up,” he repeats.

The Girl leans against the wall as she heaves herself to her feet. Huddling behind him in the street are two dozen other shivering, naked women and girls, their bodies blending together like layers of an enormous slab of graying meat4. Most are hiding their faces and weeping in shame, but some others like Jin Yi and Auntie Shu Ling are staring blankly at nothing in particular.

“March!” The official orders.

The Girl scoops up her wailing brother and slips into the huddle beside Jin Yi, who, for the first time in her short life, cannot lift her head to meet her friend’s eyes. No one speaks as they follow the official and his five cronies, each one carrying clubs or bent pipes. Soon, the sound of her brother’s wailing gives way to the sound of tiny, chattering teeth. The cold is so painful she feels as if she’s burning alive.

The banquet hall. The steaming cauldrons. The phoenix tail flags. Honey and oil. Wine splashing. Bone dice. Her brother laughing. Laughing. Laughing.

Her mind repeats these images like a mantra against reality.

The phoenix tail flags. Her brother laughing. Bone dice. Steaming cauldrons. Hall. Banquet. Oil and honey. Wine drowning everything. Laughing. Laughing.

They arrive at the furnace fields. A sliver of sun clings tremulously to the Western horizon. She licks the tears trailing down her brother’s cheeks.

Cauldrons breaking. Bodies spilling. Dice laughing. Click. Click. Honey dripping. Sweetness burns. Oil dances. Leaps. Sssssssss. Her brother falling.

“Get to work!” The official barks, pointing at the mounds of coal piled beside each furnace.

“Where did this come from?” Auntie Shu Ling croaks. “Where was this when our infants were freezing to death?”

“Doesn’t matter,” the official spits.

“But we’re done for the day!” Someone else cries.

“Lies!” He nudges the woman forward. “If you’re done, why has the coal not been touched?”

“I—I—”

“Selfish, lazy animals,” the official sneers. “Relaxing when you have a quota to meet.”

“But we’ve met the quota,” Jin Yi exclaims. “Last month. Didn’t we?”

A thin smile twists his lips. “According to one elder, some women from the village,” he sweeps his arm over the shivering crowd, “stole and destroyed over half of our steel supply last week, which is why—”

“You’re lying!” Jin Yi shouts. “How can anybody believe—”

The official picks up a poker lying close to the mouth of a furnace and jabs it into Jin Yi’s neck. The Girl cups her brother’s ears to shield him from the screams that follow. Jin Yi crashes to the ground, gasping loudly, her eyes bulging.

“Which is why you’re only halfway done,” he continues. Then, almost as an afterthought, he turns and kicks dust into Jin Yi’s wound. “As a result, there must be consequences. An example to be made.”

“How much more do you expect?” Auntie Shu Ling asks.

He names a figure that sends gasps rippling through the crowd. The Girl stares blankly back at him.

“That’s double the original quota,” she whispers.

The official bares his teeth at her. “The quota has never changed. This was the figure we gave you from the start, and this is the figure you’re going to produce, not one kilo less. Now, stop sniveling. No country has ‘changed the sky and altered the land5’ with clean hands. Either GET. TO. WORK. Or you can freeze.”

The women disperse without another word, but The Girl pushes against their current though some try to warn her with furtive glances and though she can feel the eyes of the bearded official following her.

She gets to her knees beside Jin Yi, who—upon seeing her friend’s dangling breasts—scrunches her face into a silent sob.

As The Girl gently brushes the dust from her friend’s wound, the mantra of images disappears from her head at last, like a spell that’s been undone, and for the first time since her parents died, The Girl weeps, not out of humiliation or fear but because of how foolish she feels for trying to live in a dream that does not care about her or anyone else whose head it has bloated to the point that they see banquet halls where there are only barren fields.

Jin Yi lets The Girl haul her to her feet and guide her blindly to a furnace, where she begins to mechanically move the coal.

When the Girl reaches her own furnace, she begins to sing a folk song her mother taught her years ago, almost inaudibly at first, then louder and louder:

Lush grass grows on the ancient plain Each year it withers and flourishes Even wildfire can't burn it out. It re-grows in the spring breeze.6

Something hard and bony smashes into her temple. She stumbles and finds the bearded official sneering down at her. She wonders if she might pass out from the explosion of pain when a sound, low and mournful, like that of an Erhu instrument7, suddenly fills the air. She lifts her head and realizes it’s Auntie Shu Ling.

“—on the ancient plain, / Each year it withers and flourishes.”

Jin Yi belts the next verse. “Even wildfire can't burn it out.”

One of the official’s cronies, a short man with thick glasses whom The Girl recognizes as a former classmate, cuffs Jin Yi in the ear, but this only makes her sing with even more fervor.

Soon, all the women join them, their voices mingling with the sounds of crackling fire and scraping metal.

Lush grass grows on the ancient plain Each year it withers and flourishes Even wildfire can't burn it out. It re-grows in the spring breeze.

Something—maybe surprise, maybe confusion—flickers across the face of the bearded official, and he motions for his younger accomplice to stop. He and the rest of his men drag their pipes and clubs behind them as they head for the edge of the field.

The Girl picks up the shovel as her brother exclaims, “Candy! Candy!”

She swivels around to find Grandpa Zhou flashing her a sly grin, his eyes conspicuously gliding up and down her body.

“Candy! Candy!” Her brother wails.

“So,” Grandpa Zhou bends down and hands her brother a piece of yellow candy, “I see you’re one of the women they chose.”

He sticks a cigarette through the gap where his two front teeth once occupied. The Girl frowns as she watches him light it with a red, plastic lighter. The last time she’d seen a lighter had been Fall…in the hands of the bearded official. He clicks it over and over in a bored manner.

“How much did they give you to tell them what they wanted to hear?” She demands.

Grandpa Zhou throws his head back, releasing a horrible, hacking sound that The Girl recognizes as his most genuine laugh.

“Eight kilos of rice on top of my usual ration8.” He removes the cigarette and spits. A glistening glob of reddish yellow lands by her feet. “Oh, stop glowering. You’ll be grateful for what I did in a week when you get to have porridge with me while everyone else is fighting over wild grass and dog shit9.”

“You’re a demon,” she snarls, her hands shaking so hard that she drops the shovel, “You’re a demon from the first time you touched me. I’d rather starve than have a drop of your food.”

Grandpa Zhou looks thoughtful for a moment. “Remember when I said we haven’t heard the last of Henan?” He asks. “Lao Mu, who drives a delivery truck for some government bureau just went through Henan, and you know what he saw?”

Grandpa Zhou sucks deeply on the cigarette and sighs satisfactorily. “Half a dozen starving men and women laying side by side in the middle of the road, their arms linked together, in a pathetic attempt to stop the next vehicle that passes through their town, so they can beg for food.”

He leans closer, almost as if about to share a secret. “He says they were so gaunt, so weak, none could move. He had to carry them, one by one, off the road just so he could keep driving. A few hours later, after he’d reached his destination, someone told him another driver wouldn’t have been so cruel—he’d put them out of their misery and carried their bodies home to make soup for his sick wife.” He blows smoke into her face and concludes, “Don’t think you’re any better than the people of this story, child. Don’t think you’re any better than me.”

As he begins to laugh again, The Girl picks up the shovel and slams it into his groin. The old man grunts and doubles over, breathing raggedly. By the time he straightens himself, that sly smile has returned.

“You’ll see,” he rasps, flicking her nipple. “You just wait and see.”

The Girl waits until he’s out of sight before daring to turn around. Then, she dives for the ground where her brother is lying, still sucking though the candy has already dissolved. She hugs him and starts to cry, her tears and snot matting his soft hair into sticky strands.

“I miss them.” She whispers. Then, more desperately, “I miss them. I miss them. I miss them.”

Suddenly, her brother cries, “Oops! You died!”

“What?” She lifts her head and sees that he’s pointing at something behind her.

“Oops! You died!”

Realization dawns on her. “Sparrow,” she whispers.

Setting him down, she carefully turns around and spies the frail creature shivering beside the pile of coal. She breathes a sigh of relief on noticing its twisted leg. At least it won’t fly away. With practiced hands, she wrings its neck and sets it as close to the fire as she can without it burning. She gets to her feet and shovels coal into the furnace just as one of the officials passes by.

An hour later, she and her brother devour the charred bird—nails, beak, feather, and all. Afterwards, she rocks her brother asleep then places him by the coal, on the same spot where they’d found the sparrow.

The meal returns some clarity to her head, and she uses this precious strength to think.

What had Grandpa Zhou said? Eight kilos of rice…Eight kilos of rice…

As she sucks the blood, grease, and dirt from under her fingernails, a wisp of a plan swirls inside her head, growing clearer and brighter with each round.

She looks in the direction where Grandpa Zhou had stomped off.

Stars crown the hills, winking coldly down at the mortals they govern. Pity stirs in her chest as she recalls that one night, so many moons ago, when she had dreamed that she ate the stars like they were grains of rice. Why had there been no one to slap her awake and squeeze the stars from her mouth before she’d swallowed them?

The Girl searches for an answer but finds none, so instead, she joins the chorus of singing crickets, her voice as dry as a shattered leaf.

Lush grass grows on the ancient plain Each year it withers and flourishes Even wildfire can't burn it out. It re-grows in the spring breeze.

As she sings the last note, The Girl concludes that maybe Grandpa Zhou is right…maybe no one in this world—not her nor Jin Yi nor Auntie Shu Ling nor even her brother if he was a little older—can be better than the people in his story. No one would—could have done differently.

Which gave her all the more reason for carrying out her plan.

Sparrow Bones (Part III)

It’s April, 1960. The soft pattering of rain surrounds The Girl as she squats on the edge of the deserted fields, slinging handful after handful of mud into her mouth1. The cold is so numbing that she can hardly feel the gravelly texture chaffing her tongue nor savor the hints of iron that flavor each bite. Just last week there had been wild grass and brambles to boil into a mush. Now, even that is gone.

This image of The Girl swirling a chunk of salt in a pot was inspired by a story my mom told me. During the height of the famine, my grandmother’s mother would swirl a chunk of salt in a pot of water with a pinch of rice, and that would be their meal of the day. They were lucky if each person in her family got to drink a few grains.

People would sometimes pretend that a recently deceased family member was still alive so they could collect their ration. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/01/china-great-famine-book-tombstone

One of the purposes of the Great Leap Forward campaign was to abolish all forms of private property, including land, tools, and food. https://www.britannica.com/money/topic/Great-Leap-Forward

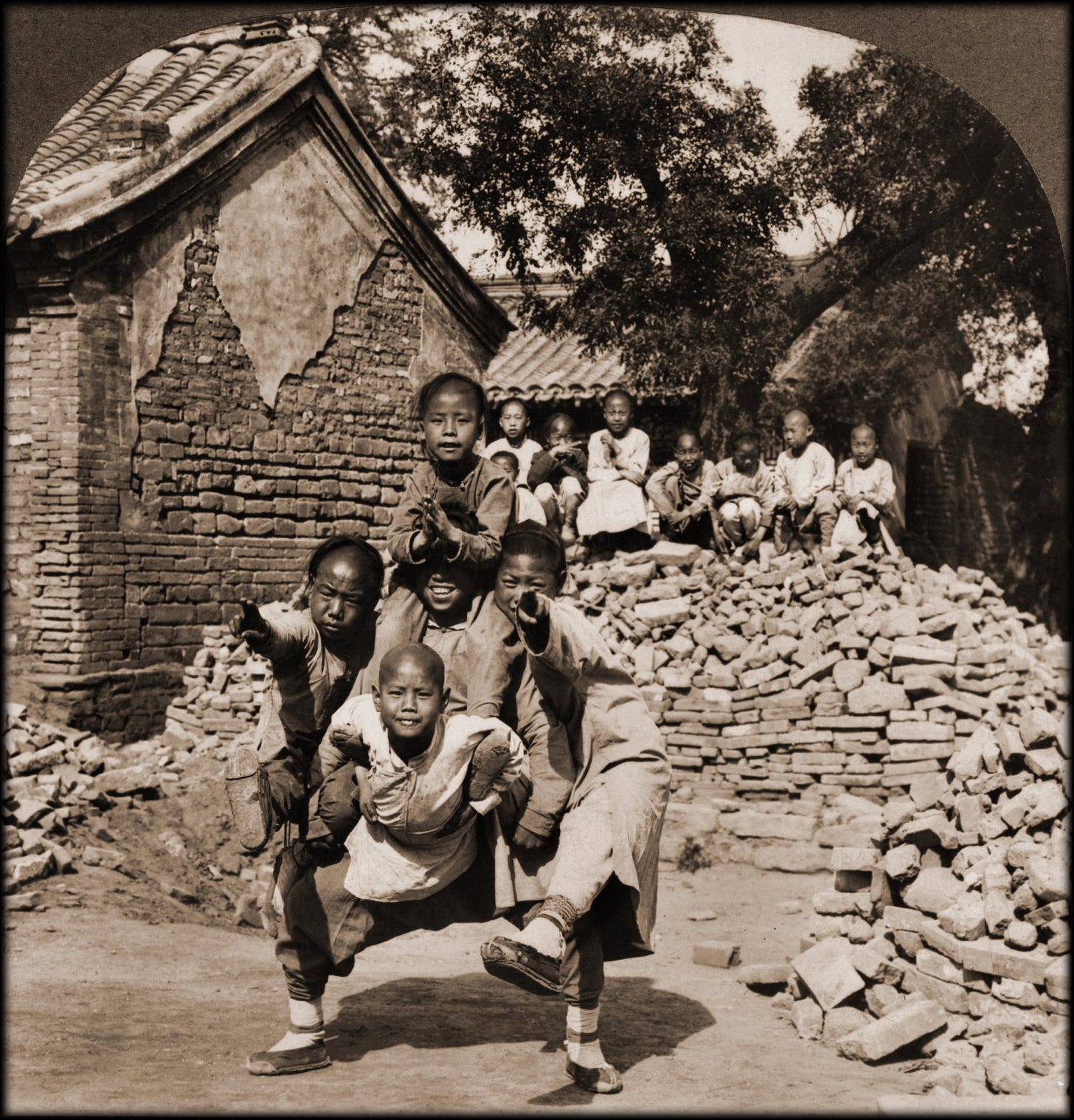

In Henan Province, the officials stripped women and girls of their clothes in winter to force them to work harder to meet the inflated steel quota. The harder they worked, the warmer they stayed, and the higher their chance of survival. Those who survived this abuse claimed it was the worst humiliation they had ever suffered in their lives. Source

This is a slogan used in the 1960s by the Communist Party to inspire peasants to work harder in order to become self-reliant. Though the slogan was created about a decade after the Great Chinese Famine, I wanted to include it in the story to give an example of the type of slogans the party used to influence the population at the time. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Learn_from_Dazhai_in_agriculture#cite_note-4

This is a Chinese folk poem/song written by Tang Dynasty poet Bai Juyi in 772-846 BC. I wanted to use its imagery of renewal and hope to capture the women’s resilience in the face of such inhumane treatment. http://www.chinesefolksongs.com/fugrave-deacute-g468-yuaacuten-c462o-sograveng-bieacute-farewell-on-an-ancient-plain.html

Betraying friends for extra food was not uncommon for this time period. https://www.publicbooks.org/famine-fiction/

People would scavenge grass, leaves, tree bark, and sometimes even dirt to survive. https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/chinas-great-leap-forward/

Really glad to have connected with you. Love your work, keep it coming!

Really well done Macy. I felt I was there. Looking forward to future works.