What Cherry Blossom Season can Teach Us about Life, Loss, and Change

Truths I learned while exploring Osaka and Kyoto for five weeks

Hi friend!

How are you doing? Apology this newsletter has been in the works for so long. My travel schedule got a bit more intense than I’d expected towards the end of my Japan trip, which, unsurprisingly but also unfortunately, cut into my writing time.

Over the last two weeks, I’ve bounced from Osaka to Kyoto to Tokyo and then back to Osaka again. I arrived in Seoul just a few days ago and have finally begun to step on the brakes, albeit not as hard as I probably should. As of writing this newsletter, life still feels like a rollercoaster, just a less dizzying one.

Though I can’t wait to share this new chapter of my adventure with you, I’m not finished writing about Japan just yet. Thus, as a heads up, you might start seeing a mix of both Japan and Korea-related content populating your inbox soon.

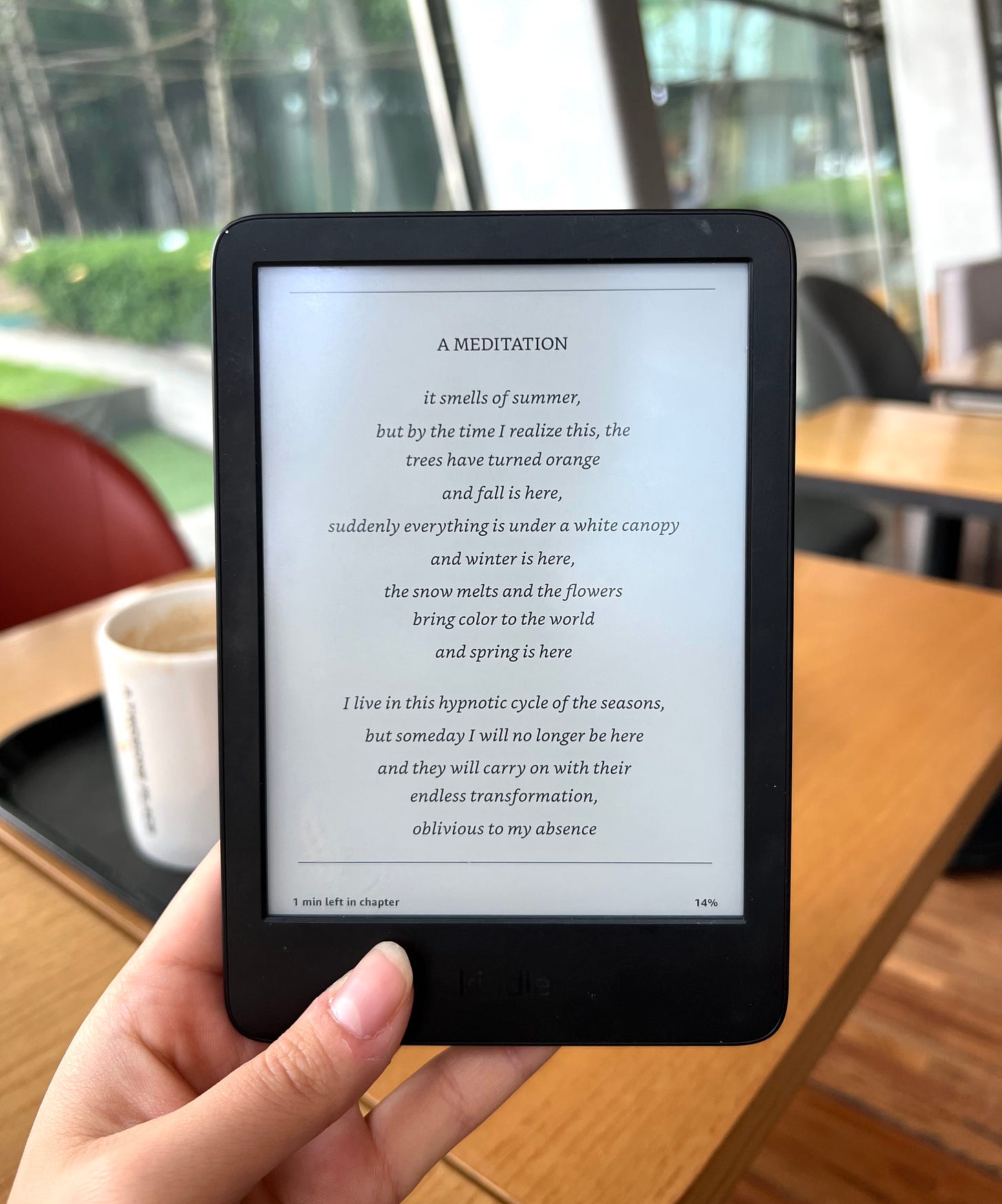

That said, today’s newsletter is a culmination of a weeks-long meditation on the parallel between the brevity of the Sakura season (full bloom lasts about two weeks at most) and our own fleeting mortality.

I hope the ideas peppered throughout this article will spur you along on your journey of growth as much as they have been spurring me on mine. Or at the very least, I hope you enjoy the collection of 4k pictures of cherry blossoms woven between the paragraphs. (Based on the feedback I received on our previous article, I’ll be incorporating more visuals into this newsletter from now on.)

Lastly, if there’s any part that particularly resonates with you, feel free to leave a comment or send me a message by replying to this email. :)

Word Count: 2,100

Reading time: 7 minutes

P.S. Several women writers are offering their books for free this month. If you're looking to expand your Spring reading list and want to support women writers, check out the promo here.

What do you picture when you hear someone say “cherry blossoms”? A canopy of lush blossoms hanging over a winding stream? Delicate branches framing a glittering metropolis? Petals drifting in the wind against a backdrop of lush green hills and valleys?

I bet that most of us when asked to think of cherry blossoms, or Sakura, picture them at the height of their vitality, their branches laden with clouds of pink and white. Such tableaus epitomize our contemporary standards for beauty. We laud youth and strength. We envy those with new clothes, new cars, and new gadgets. We strive for perfection and in doing so we curse ourselves with trying to find happiness in stagnation.

On the opposite end of the spectrum lurks age, loss, and death—painful reminders of our mortal transience. We mask our imperfections with powder, scrub away our wrinkles with creams, and harden our softening tissues with injections.

As of 2021, the anti-aging market was valued at 62 billion USD; by 2027, that figure is expected to climb to 92 billion. In a society that prefers the illusion of eternal youth over the celebration of the natural human life cycle, is it any surprise that we’re willing to pour so much time and resources into preserving that illusion?

As I watched Sakura across Osaka and Kyoto bud, burst alight, and then fade in a flurry of petals, I realized that beauty exists as much in life as in death, as much in the anticipation of an event as in its conclusion.

Blooming for a mere ten days on average, the Sakura's lifespan chafes against our contemporary standards for beauty. We like to think of beautiful things as unchanging, like a fossil frozen in amber, unmarred by the currents of time.

A new car with a gleaming coat of paint is more beautiful than an old car with a scratched hood and rusted bumpers. A springtime garden bursting with color is more beautiful than a patch of bare gray soil. A youthful body with firm muscles and lustruous skin is more beautiful than an aged body marred with wrinkles and scars. Such are the values our society have been pounding into our brains from the moment we are old enough to recognize the difference between “like” and “dislike”.

But must beauty always correlate with youth, stagnation, and perfection? Can beauty be found not only in the preservation of life but also in the graceful shedding of it? To answer this question, let’s meditate on the life cycle of the cherry blossom.

Because Sakura blooms for such a brief period, if you were to take a picture of a Sakura tree on Monday and then a picture of the same tree a week later, the scenery could look markedly different.

While in Osaka, my favorite place to enjoy cherry blossoms was Osaka Castle Park, home to some 3,000 cherry blossom trees. I went a few days after they’d just bloomed. If you looked up at certain places in the park, the canopy of blossoms was so thick that you could barely glimpse the sky. Picnics among friends and family filled every available patch of earth. Blossoms trickled from the branches, falling into people’s hair, drifting over the pavement, and flowing downstream in the moat.

By the time I returned late next week, the once verdant grass had become a pointillist canvas of white and pink. Brown tinged the outline of the petals that had fallen earlier in the season, heralding their impending decay. Blossoms streamed from half-bare branches like tears. Everywhere, tender green leaves were already beginning to crowd out the blossoms.

In Japanese culture, Sakura is cherished not in spite of its brevity but because of it. The flowers’ transient blooming period poignantly mirrors the fragility of our own lives. We may be here today, but what about tomorrow? Or the day after?

Longing for an idealistic past is like staring up at bare Sakura branches and mourning the loss of their blossoms while ignoring the beauty of the petals swirling on the ground around you. Accepting the ephemerality of life frees us from fearing the passage of time. Ceasing to undo the effects of everyday change and loss allows us to be at peace with the present even when the present feels less ideal than the past.

In basic economics, the supply of a resource correlates with its value. The limited availability of limited edition items and luxury goods is what drives up their price. Similarly, our mortality—the limited time we have on earth—is precisely what makes our lives so precious.

Just as every petal that falls to the ground can never return to the branch from which it came, neither can we recreate a single moment of our lives. Every second that passes is lost forever. We can try to revive the emotions associated with a cherished memory by returning to the location where it took place or by repeating a sequence of actions, but we can never truly relive that exact memory. The world has changed too much since. We have changed too much since.

Even the person you were a few seconds ago is not the same as the person you are right now. A few seconds ago, you hadn’t absorbed the information from that previous paragraph. Now, you have. You might only have changed by a minute degree, but you did change.

Compounded over time, these small changes—staying overtime at work even when don’t need to, running an extra mile, deciding to read some random girl’s newsletter on the internet—have a greater effect on your identity more tangibly than once-a-decade epiphanies. Each moment is different from the rest not only because the world has changed but because we too are also constantly changing.

The Japanese aesthetic of Wabi Sabi emphasizes appreciating the imperfection and transience of things, or, as I’d like to phrase it, appreciating reality as it is. I first encountered the term in a video essay on filmmaking a couple of months before I set sail for Japan. Since then, I’ve been contemplating the term in my day-to-day life, trying to redefine my understanding of what makes something beautiful and valuable.

In Wabi Sabi: The Japanese Art of Impermanence, Andrew Juniper defines wabi sabi as "an intuitive appreciation of ephemeral beauty in the physical world that reflects the irreversible flow of life in the spiritual world.”

In Wabi Sabi: The Wisdom in Imperfection, Nobuo Suzuki explains that “for a Westerner, even for a Chinese, the most beautiful cup is an impeccably fashioned one…In Japan, however, the most highly-prized cup—and the most expensive—tends to be the one that contains flaws, because that makes it unique…

“Applied to humans, being aware of our imperfection makes us humble; accepting it frees us from being unhealthily self-demanding and from the fixation on a perfection that does not exist in nature and by extension does not exist in humans either.”

To strive for perfection is to believe that in a reality of constant, inexorable change, it is paradoxically possible to reach a point of stagnation where change is neither necessary nor possible. To reach for perfection is like trying to force a Sakura tree to remain in full bloom past its time—it’s delusional, impossible, and unnatural.

Even as I’ve been learning to appreciate loss and imperfection—withering petals blowing across the pavement, the tarnishing of my favorite earring, scratches marring the back of my Kindle—I still find myself struggling to incorporate Wabi Sabi philosophy in one of the most important aspects of my life: relationships.

As a nomad, I lack the means of establishing and nourishing long-term friendships. Over the past three months of traveling Japan, I’ve had dozens of amazing, relatable, kind individuals cycle in and out of my life.

When I left Tokyo back in early March, moving on from the life I’d started to build there and letting go of the people I’ve come to cherish was strikingly painful. My first few days away, I wanted nothing more than to rewind the clock and return to the status quo.

Nowadays, through a combination of watching so many friendships bloom and fade as well as becoming more comfortable with the Wabi Sabi mindset, I’m beginning to fixate less on what has been lost and appreciate more of what I’ve gained from these (albeit brief) friendships—intercultural empathy, solidarity, wisdom, inspiration, and hope.

Learning to be ok with allowing a person to fade from your life begins at the start of your friendship with them. In the past, I would try to ignore the reality that the people I currently cherish won’t remain in my life forever because facing it was too painful. Now, I enter into friendships by centering my mind around this truth.

Being wary of—rather than ignoring—the inevitability of our mortality, the maturity of our personalities, and the evolution of our circumstances allows me to enjoy the beauty of the present without the burden of fearing the change to come.

In learning to accept impermanence and imperfection as a part of my everyday life, I’ve also learned to accept—even celebrate—the process by which a thing or a relationship diminishes.

One of the key determinants of happiness is being grateful for what we already have, but why limit that attitude to only material things? Why not also appreciate the time we have to live this life?

Two weeks ago, sprawled beneath the Sakura at Osaka Castle and laughing with two strangers I’m lucky enough to briefly call friends, I realized that just as the petals swirling like snowdrops above our heads are no less beautiful than the petals still fixed to the branches, neither is the twilight of my friendships less beautiful than the climax.

There is joy in making friends and watching your lives intertwine. There is also joy in watching them move on and continue their journey of growth without you. As I have learned over the past year and a half of traveling, we can either be present in the present or squander even the limited time we have in the present by longing for a past that no longer exists or a future that is not guaranteed to come.

To see the beauty of something that isn’t conventionally beautiful requires you to appreciate its present reality without comparing it to what it once was or what it could be.

It’s to admire the way a dead leaf is delicately curled without wishing it was still as lush as it was in its youth. It’s to treasure the chip in your favorite mug because that flaw makes it different from all the other mugs with the same design. It’s to see the maze of wrinkles on the back of your hand as a biological artwork rather than a reminder of irretrievable youth.

Just as the petals swirling like snowdrops above our heads are no less beautiful than the petals still fixed to the branches, neither is the twilight of my friendships less beautiful than the climax.

Now, if you were to ask me to picture “cherry blossoms”, I don’t just think of one stagnant, postcard-perfect image. I think of a series of images building on one another like scenes on a scroll.

I think of stark tree boughs stretching infinitely against a pale wintry sky, of pink buds clustering at the tips of delicate branches, of a canopy of pink and white flowers swaying to the tune of a gentle spring wind, of a leafy, green tree ringed by a carpet of wilting petals.

When we think of beauty as a stagnant, unchanging ideal, we become obsessed with preserving what is and regressing to what has been. We chafe against Mother Nature’s inherent desire to progress and mature and change. To exist in this constant state of strife is to curse oneself with perpetual discontent.

But what if we approached the concept of beauty with a more holistic perspective? What if rather than clinging to a single moment, we unfurled the rest of the scroll and learned to appreciate the beauty of an object, a person, or a relationship in every stage of its life cycle?

Loss and change are hard. They’re hard even if you learn to see them in a positive light. But they’re also what makes every moment of our lives—no matter how tedious—invaluable. No two moments are the same. No life once lost can be reclaimed. Some might see mortality as a curse, a thing to be frightened of, but I see it as a gift that makes life worth living and tomorrow worth pursuing.

We can’t control how long we have to bloom, but we can control how passionately we do. In the end, when you unfurl your scroll of memories one final time, will you be greeted by a slate of monotonous gray or a landscape of vivid colors? The brush is in your hand, the palette beside you. All you have to do is choose.

A lovely post, Macy! and I'm glad that you seem to have had a rewarding time in Japan.

I don't want to admit to skipping through to just look at the gorgeous photos but I thought these were breathtaking. The world is beautiful sometimes.