My St. Augustine Trip: Exploding Bishops, Exploring Old Buildings, and Existentialism

A Weekend in America's oldest city!

No time to read? Listen to it instead. :)

Prior to researching Florida, I’d thought that the oldest city in the U.S. has got to be either Jamestown, Virginia or Plymouth, Massachusetts buuuuut as it turned out, neither of them gets the trophy. That honor falls to St. Augustine, which was founded by the Spanish in 1565. For context, Jamestown was founded 42 years later in 1607 while Plymouth was founded 55 years later in 1620.

Being an enthusiast of historic sites, distinct architecture, and old (sometimes quirky) buildings, I couldn’t resist the city’s allure. It is one of the main reasons why I decided to make Palm Coast my “home base” during my time in Florida. Although much of the original buildings before the 1700s were destroyed during the British takeover, the street pattern and architectural aesthetics are still faithful to the original town plan from the late 1500s. In fact, it’s home to the narrowest street (only 7 feet wide!) and the oldest wooden schoolhouse in the nation.

This original layout is especially noticeable in the Historic Colonial Quarter, where I spent most of my hours during my two-day visit. If you’re listening to this article, I want you to close your eyes, relax, and just imagine.

Narrow, cobblestone streets polished smooth from the millions of shoes that have grazed its surface. Colorful stone buildings bearing as many hanging flowers as American, British, Spanish, and a mix of other colonial-era flags. The scent of smoked salmon, oven-hot pizzas, and Cuban empanadas wafting from open doorways, beckoning you to draw closer. The sound of boisterous chatter and the occasional twang of a street instrument as you weave through the crowd, passing families with strollers, couples walking hand in hand, groups of friends just having a good time

At the same time I was submerging myself into this whirlpool of stimulations, I was also grappling with a growing sense of melancholy. As strange as it might sound, I’ve never really explored a place—be it a region, a town, or a city—by myself before. When I say “by myself”, I mean it literally. No other Workawayers. No Workaway hosts. Nada. Just me, myself, and I. Watching the ebb and flow of strangers around me, I’d never felt so alone before.

Unlike arriving at college, where everyone is actively—some would say desperately—trying to make friends, here, nobody takes much interest in you other than to say “excuse me” as they pass by. When you see something interesting, when you get excited or frazzled, there is no one you can turn to release these thoughts and emotions. Self-expression is limited by your skill with a camera. Meanwhile, the only conversations you have access to are the ones between you and yourself. You are as untethered to the souls around you as a leaf fluttering in the wind.

I felt this “untetheredness” even while visiting my first destination, the Castillo de San Marcos. Originally built by the Spanish in 1695 to defend St. Augustine against pirates and other foreign powers, this star-shaped, stone fort is the oldest in the U.S. Throughout its lifetime, it’s served as a base for Spanish, British, Confederate, and American forces before finally retiring as a national monument in 1933.

Walking through cool, stone chambers and snapping photos of carefully placed props, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of slight disbelief toward the fact that once upon a time, its courtyard had echoed with the chatter of soldiers; its roof had shuddered with the BOOM of canons; and its windows had felt the breaths of hundreds of Native Americans as they peered hopelessly towards a freedom they would never get.

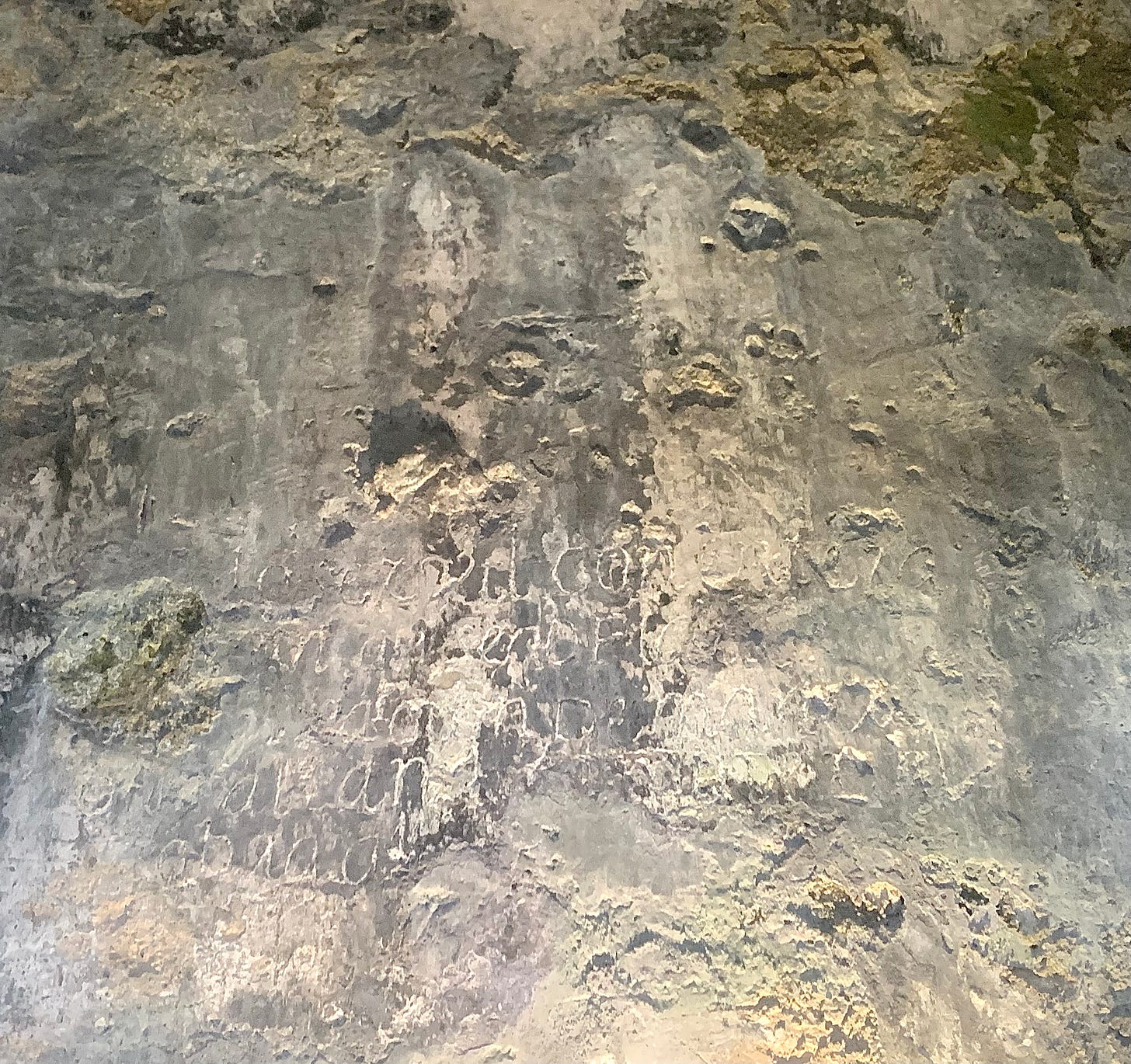

Ephemeral as individual humans are, we have our ways of leaving our marks. You can’t help but feel a shiver slither down your back when you touch the bullet holes on the castle’s execution wall, knowing that each one of them had gurgled with the blood of long-forgotten prisoners. You can’t help but slightly panic as you stand in the secret dungeon, listening to the echoing shouts of the couple that was buried alive there. Nor can you keep yourself from leaning with intrigue towards the mystery writing scratched into the wall of the soldiers’ barracks. In each case, history is literally carved into stone.

(I didn’t get a good picture of the dungeon, but you can check it out here.)

One reason why I remember these aspects of the castle more vividly than others is because I’m drawn to experiences that bring me closer to the historical figures that had once occupied the space that I am now occupying. As morbid as it sounds, somehow, feeling the presence of death makes history feel more real. Or in other words, it makes the past feel less disconnected from the present.

Maybe it’s because one of the strongest links between the dead and the living is our mortality. One day, we too shall be like the prisoners who died by gunfire or the lovers who passed away in each other’s arms—Remnants from a past that was once alive and bustling but now, in the future, are nothing more than stories and dust. What marks will you leave when you’re gone? What will future generations make of them?

As I picked my way around the courtyard, I realized that one of the advantages of exploring a place alone is that you are master over your time. You don’t feel guilty for slowing down the group by stopping to take photos every few minutes. You can glance at an artifact and decide you’d rather move on without worrying about leaving your friends behind.

In hindsight, I’m fairly convinced that exploring alone was what allowed me to probe the subjects of history and existentialism as earnestly as I did. Without the pressure of a definite itinerary, I was able to engage with my setting on a more intimate level that, at the end of the day, deepened my adoration for the archaic.

Around 9 pm on my first night, I wound up taking a two-hour ghost tour through some of the city’s most allegedly haunted sites, including the Castillo’s moat, two graveyards, and a couple of restaurants and bars.

My tour guide was a lanky man whose affinity for swearing was only outmatched by his flair for storytelling. In other words, he was exactly like a tour guide for these kinds of tours should be. Though each of his stories was memorable in its own right, the one that haunted me the most was the one about what happened at the funeral of the first bishop of St. Augustine.

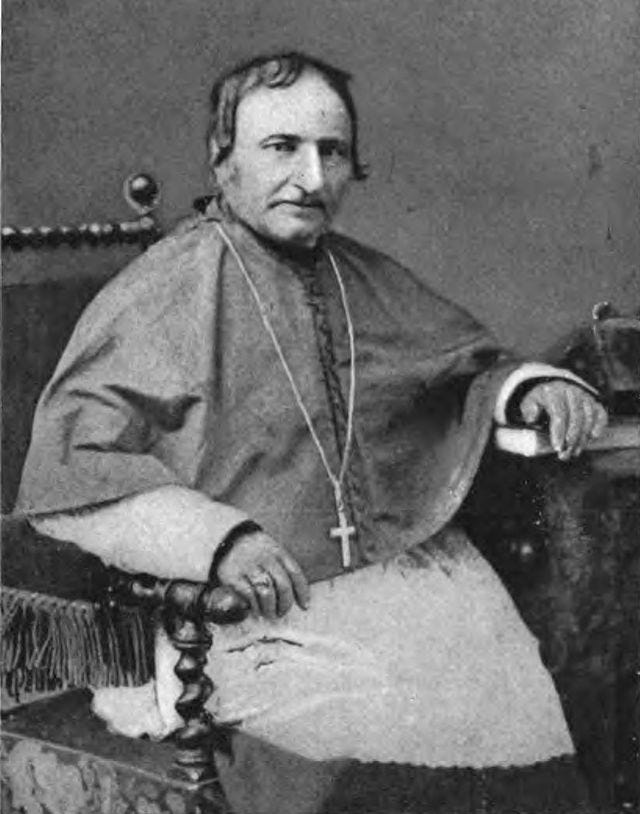

Bishop Augustin Vérot was appointed bishop of St. Augustine in 1870. His efforts at establishing schools and churches as well as reviving the memory of Florida’s early martyrs quickly made him a beloved public figure. The tragedy of his death six years later was felt community-wide, resulting in a two-week-long mourning period and finally the funeral.

The problem was he’d died in mid-June. As you can imagine, preserving a corpse during the height of Florida’s hot season was no easy task without refrigeration. I don’t even want to begin imagining what the Bishop smelled like by the time his funeral rolled around.

Being as popular as he was, everyone in town wanted to view him before he was returned forever to the earth. Thus, an iron casket with a hermetically sealed glass top was created for the occasion and the bishop was placed inside. Unsurprisingly, the viewing went on for quite a long time, and before long a fog began to thicken on the glass, so much so that soon it obscured the bishop entirely. At the same time, an audible hissing noise permeated the crowded courtyard as the coffin began to rattle, like the dead was coming back to life.

In a split second, the coffin exploded. Thousands of pieces of metal and glass flew in every which direction and along with them, you guessed it, steamy, mushy pieces of the bishop. It splattered onto people’s clothes, their hair, and even their faces. Yum. As you can guess, the funeral proceeded much faster after that event. Before you know it, the bishop—or at least, what’s left of him—was dropped in the ground, and the people ran home to literally wash the taste of this day from their mouths.

History is also far more interesting when you get up close and intimate with the details. Wars, political alliances, and sweeping cultural shifts—you know, the kind of stuff we learn in school—might have shaped history on a global level, but they’re not what titillates most people’s imagination and interests. Such information feels cold and removed from our lives.

Throw in the experiences of individuals and that’s when the game changes. That’s when history becomes tangible, and you’re transported from the comfort of your 21st-century life to a crowded Cathedral courtyard on a balmy summer day, your palms pressed against the fogged glass of a trembling coffin, your ears tingling with the sound of whistling steam. In such moments, the past feels almost as alive as the present. We don’t relate to plain facts such as when the funeral took place or where the coffin is buried. We relate to people, even if they’ve been dead for centuries.

But there’s something even more powerful at resurrecting history than learning the stories of individuals: Physical connection with the past. Standing on the stones where the funeral took place, your story has, in a way, briefly intersected with the Bishop’s, and once again, you are reminded—as you were at the Castillo—that in the end, our time on earth is nothing more than stories and dust. Even if you were to build an indestructible monument to yourself, no one would understand the significance of that monument unless they knew your story. (Fun fact, I learned this from the poem “Ozymandias” when I was seventeen. 10/10 recommend.)

As entertaining as learning about historical figures is, that’s not the main reason why we study history. We look to the past because change often follows the same pattern. You’ll see what I mean later on. That’s something I realized while visiting the final destination of today’s post, the St. Augustine Lighthouse & Maritime Museum.

Though its candy-cane facade looks freshly painted and its equipment is up to date, the lighthouse’s origin goes back several hundred years. In fact, it started as a wooden watchtower in the 1580s, not far from its modern location. Over the next two hundred years, the Spanish would reinforce and heighten the tower with wood as well as another popular local material called coquina, which is basically rock made out of millions of calcified clam shells. The photo above features the final iteration of the St. Augustine Lighthouse completed in 1874.

Regardless of whether it was a petite, 30-foot watchtower or a looming 165-foot lighthouse, it was always lit in the same fashion: Someone, usually the lighthouse keeper, had to climb to the top to manually light the flame. While exploring the interior, I got to see the oil bucket of the final keeper, which when filled could weigh up to 30 lbs. Imagine carrying that up 219 steps twice a day for years. (That’s one way to get fit without a gym membership).

Such was the routine for dozens of lighthouse keepers from the lighthouse’s inception till 1935 when the power of electricity and automation finally outshone human labor. For context, this shift was not unique to St. Augustine. Throughout the next decade, it would permeate lighthouses across the world. Today, there are 779 lighthouses in the U.S. but only one, Boston Light, is still manned by a traditional keeper. After thousands of years of humans manually lighting the way for seafarers, the era of the lighthouse keeper had finally come to a close.

Though technology is amazing and convenient and life-changing in its own right, it kinda grieves me to see it disrupt this ritual that’s been passed down through generations and across civilizations. By replacing the lighthouse keeper with an operating system, there’s no one left who can empathize with the thousands of keepers of times past. This may be a microscopic example of how modern technology is estranging current and future generations from the humanity of yesteryear, but it captures the overall pattern that we’re witnessing across the world.

History is like a spiral staircase. No matter how high we climb on the y-axis of technological advancements, we are destined to return to the same position over and over on the x-axis of human needs. Maybe that’s why we as a species are obsessed with unearthing the past.

We feel a sort of kinship to those who existed before us because we know that regardless of whether a society used wooden spears or flintlock muskets, if they went barefoot or wore Gucci shoes, they felt the same range of emotions as we feel and have gone through the same stages of life we are currently going through. Even when separated by a sea of centuries, humans are not so different that we can’t relate to each other beyond death and across time.

Exploring St. Augustine by myself gave me an exorbitant amount of mental space to meditate upon all that I was seeing, hearing, feeling, and learning—A luxury I’d never really got to taste until this trip. By the end of the trip, I’d gone full circle. Exploring alone initially made me feel untethered to the people and reality around me, but as time went on, it enabled me to cultivate a deeper appreciation for the city’s history.

So, would I recommend you to explore a city by yourself? I’d say, go for it. When you challenge yourself in this manner, you not only learn a lot about a place, but you also learn to grow more comfortaable with spending time with yourself in public. You quickly learn to shed the weight of self-consciousness and to feel whole without the protective presence of familiar faces. Though I wouldn’t go so far as to call my time in St. Augustine “empowering”, it sure came close.

What to read next…